The week of January 12, 2026, the UpGuard Research team detected an exposed Elastic database with around 3 billion email addresses and passwords, and 2.7 billion records with Social Security numbers. That amount of data suggests it was created by recombining prior SSN breaches like the OPM breach in 2015 or the National Public Data breach in 2024.

On the other hand, if even a fraction of the records were real—if only 10%, or 270 million records, or even 1% were real—the exposure would be a dire bellwether for the state of privacy in America. With the help of some unfortunate friends, we were able to confirm that at least some of it was real. And with the help of K-pop and some American presidents, we were able to approximate when the passwords were collected.

Discovery and Attribution

While most exposed databases require investigation to determine if they contain sensitive data, this one was obvious. The database had one index named “ssn” and another named “ssn2,” each containing millions of records with nine-digit numbers in a field labeled “ssn”. The database also had several indices that were collections of emails and associated passwords, sharded by first character of the email address.

That data structure—a collection of sensitive PII and plaintext passwords—suggested it belonged to a threat actor or amateurish threat intelligence vendor (both of which regularly leak collections like this). There was no identifying hostname or log files with other indicators of the owner.

On January 16, we submitted the IP address and explanation of the issue to the FBI’s IC3. We also submitted an abuse report to Hetzner, the hosting company. They replied saying they would forward the issue to the customer. After we clarified that their customer was in gross violation of privacy laws, all public access to the database was removed on January 21. Hetzner replied once more:

Problem solver for now indeed. But how much of a problem had it really been?

Impact

Verifying data breaches with Social Security numbers is tricky; it requires the identities in the data set to intersect with the people you know extremely well. As luck would have it—bad luck, I suppose—I was easily able to find two close friends.

For John Doe, there were four records with his name. Each record had a unique physical address, which I recognized as being the correct state and city, though some of the exact street addresses were not correct. Across the four records there were also three different SSNs. I contacted John Doe and he confirmed that one of them was his actual Social Security number.

I located another friend, Jane Doe, who had been the victim of identity theft in the recent past. She never learned how her identity had been compromised. I also searched for her partner, who she has lived with for years and who had not been compromised at that time, and did not find him in the data.

Interestingly, John Doe had not experienced any identity theft attempts against him. Between the two cases we had evidence that this data was actively used for identity theft, but that not all the compromised identities had yet been targeted.

Data timeframe

This data was likely the result of one or more data sets being refined and combined into a concentrate of sensitive PII. So how long ago had the data originally been stolen?

Based on a technique that we developed during this case, our best guess was circa 2015. We arrived at this using cultural index fossils in the password collections. We identified words that would likely have jumped to significant interest during identifiable time periods and measured how frequently they were used as passwords.

One test was the prevalence of two popular political figures. There are 655 non-case sensitive instances of “obama” and 265 of “trump.” Donald Trump has been a pop culture figure for decades (The Apprentice ran from 2004-2017), but since 2016 he has been a more visible figure with a more devoted following than Obama. The lower number of search results for “trump” relative to “obama” suggests large portions of this data are circa or pre-date 2016.

Applying the same method to other pop culture figures over the last 20 years tells the same story. One Direction (active 2010-16) and Fallout Boy (hit "Sugar, We're Goin Down" released in 2005) top the list. Taylor Swift, active since the early 2000s, has a noticeable number of mentions, but not commensurate to the record-setting mania of the Eras tour.

Other celebrities of today are not mentioned as frequently. By 2020, BTS had reached a level of global stardom where John Cena was an avowed member of the “BTS Army.” Prior to 2017, however, they had not achieved mainstream success in the US. Only finding two passwords matching “btsarmy” dates this to before their breakout. BLACKPINK and KATSEYE are also very popular today and mentioned far less frequently than stars that have since waned.

Admittedly, I am a middle-aged man who no longer has his finger on the pulse of what’s cool, but this looks like a distribution of what was popular ten years ago and not what my middle-school daughter talks about with her friends.

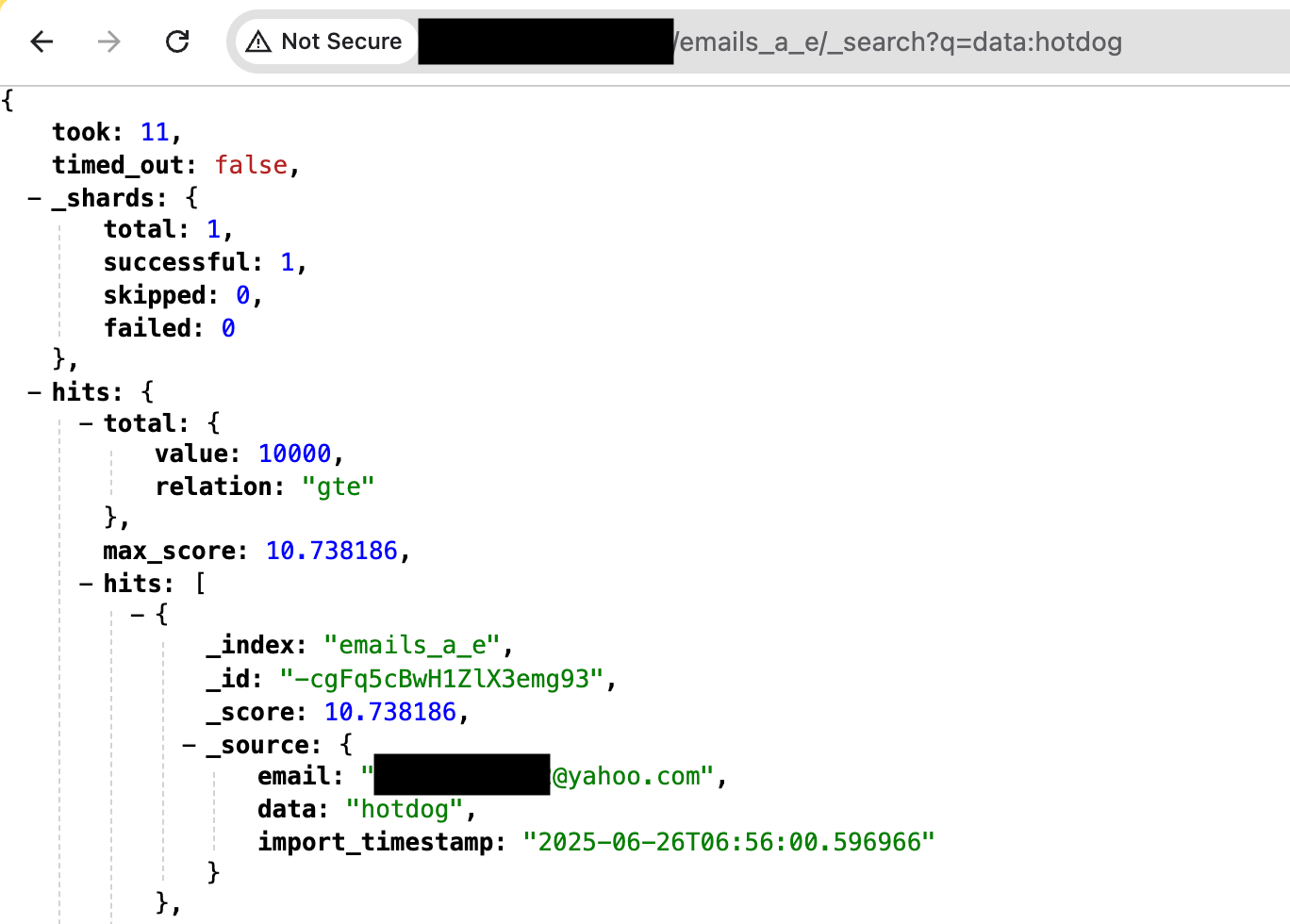

Of course, all of those pale in comparison to timeless passwords like “hotdog.” The number of results for “hotdog” hit the 10,000 result max that Elastic returns for a single query. Fandoms come and go, but hotdog is forever.

Synthetic data

Years ago a password I used was compromised and, despite no longer using it, that password will circulate in combolists until the end of time. This data set contained my personal email address and that password, along with several similar records of synthetic data presumably generated to attempt to brute-force other accounts I might have.

The variations included a downcased version of my password and switching my mail domain from gmail.com to yahoo.ca and yahoo.com. None of those permutations are valid but these records provide an interesting view inside the algorithms used by attackers to attempt to locate other accounts.

Scope

Because of the size and sensitivity of the data, we did not attempt to download the entire data set. From a sample of 2.8 million records in the ssn database, we can calculate some summary statistics.

In that sample, there were 1,062,714 unique combinations of first and last name, or about 2.6 records per person. Some of the most frequent names are also common names–there were hundreds of records for “James Johnson” and “James White”–and likely indicate different people, but without knowing their addresses or dates of birth we can’t distinguish them.

The sample of 2.8M records included 1,453,086 unique SSNs, indicating some repeats as expected from manual observation. About 52% of the records had unique SSNs and about 40% of the records had unique names. After downcasing the passwords to remove potential variations introduced by synthetic data, there were 1,759,147 unique passwords in a sample of 2,342,700, making about 75% of passwords unique.

Extrapolating out to the total data set, that would mean approximately:

- 3,036,783,212 password records * 75% unique = ~2.27 billion unique passwords

- 2,696,487,451 personal records * 52% unique people = 1.4 billion unique names

- 2,696,487,451 personal records * 40% unique SSNs = 1.08 billion SSNs

Of course, not all those records are real. For the two cases I could verify, one out of four SSNs were real. That sample is too small to extrapolate the total number of real SSNs. If we believe a quarter of a billion SSNs have been breached that would be effectively every adult in America. But the number does suggest that far more peoples’ SSNs have been compromised–millions more–than previously known.

The junk results also indicate how much inaccurate data there is in the upstream data broker and credit check systems from which this was likely taken. Some records had values that indicated real user input from unhappy people rather than synthetic attempts to guess addresses and passwords. Addresses like "EMAIL MY BILL" and "1234 EAT MY DOOKIE ST" suggest that, at some point in the lifecycle of this data, there were real end users putting data into web forms. My expired password, the 60% of SSNs that were duplicates, however many more are simply fake–all this junk data circulating like a digital garbage patch.

Conclusion

John Doe in particular was concerned, and rightfully so. His Social Security number was available to essentially any nefarious actor who wanted it and had been for years.

One of the reasons SSNs are so dangerous is that they cannot be rotated the same way as a password. What could he do to protect himself?

My best advice is what Brian Krebs has recommended in the past: maintain a credit freeze whenever possible to prevent the abuse of compromised SSNs. That may not be enough; any system that can use an SSN for authentication should ideally be reinforced with stronger authentication mechanisms you can change, like a password and MFA.

Really, there’s no reason to wait until you are at imminent risk of identity theft. As Krebs explains, credit freezes are generally good for everyone, and I encourage any readers of this article to forward his explanation to their loved ones.

For organizations handling sensitive data, this should be a wake up call to the importance of avoiding such breaches in the first place. There’s no putting the genie back in the bottle for the millions or billions of identities whose SSNs have been compromised. Even now, more SSNs mishandled by DOGE are at risk of spilling into the dark web data trade. Once they do, they don’t go away.

Protect your organization

Related breaches

Student Applications: How an Education Software Company Exposed Millions of Files

By Design: How Default Permissions on Microsoft Power Apps Exposed Millions

Sign up for our newsletter

Free instant security score

How secure is your organization?

.jpg)

.jpg)