UpGuard can now report that we have secured a Langflow instance leaking data for around 97,000 insurance customers in Pakistan, including 945 classified as “politically exposed people” due to their status as prominent public figures. Pakistan-based technology consultants Workcycle Technologies used the Langflow instance to create AI chatbots for financial entities like TPL Insurance and the Pakistan Federal Board of Revenue. Langflow is one of many new technologies developed to facilitate AI adoption, with its first commits in 2023 and a v1.0 release in June of 2024. In addition to the impacts for people in an already volatile area, this case marks the first reported data leak of an insecurely configured Langflow instance.

About Langflow

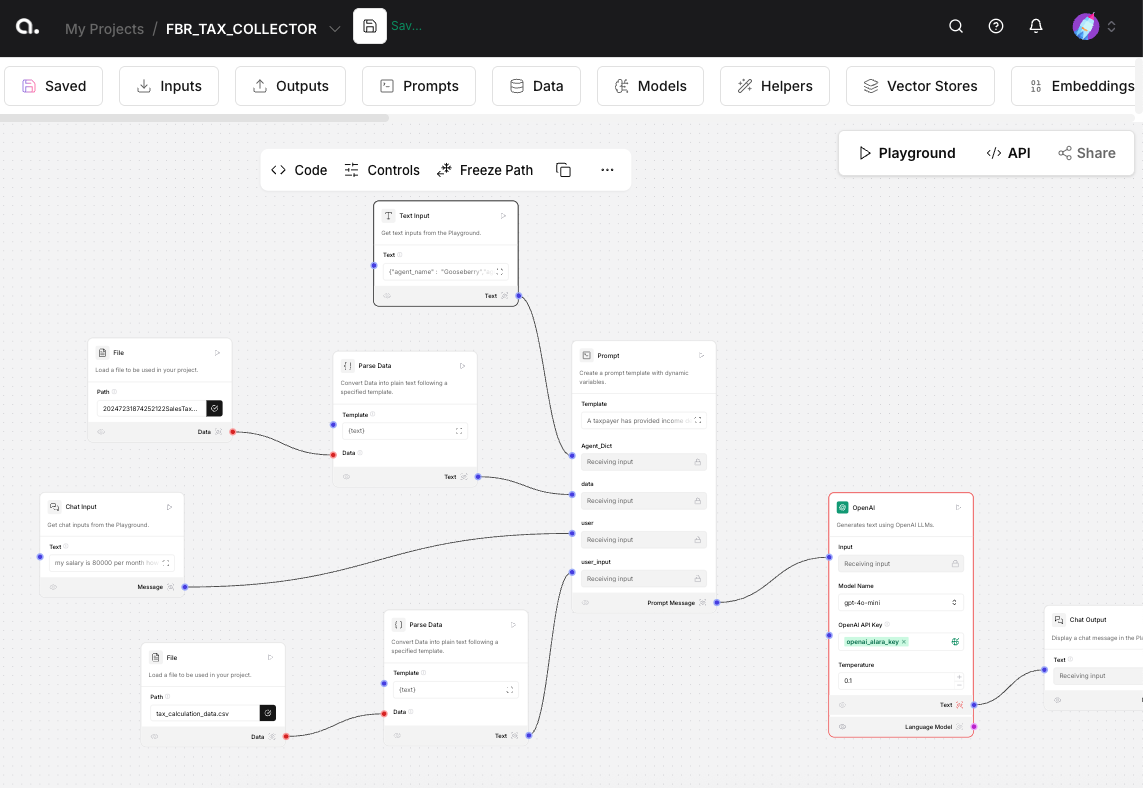

Langflow describes itself as “a low-code tool for developers that makes it easier to build powerful AI agents.” Users add data sources and models, either by uploading files or connecting to external sources, then create prompt response workflows using Langflow’s access to data sources and LLMs.

A recent Langflow vulnerability has already illustrated the perils of a platform that provides users with the ability to execute code with minimal roadblocks. That particular vulnerability was patched in version 1.3.0, but internet scanners like Shodan and Censys still show self-hosted internet-facing instances mostly running vulnerable versions.

At the time of our research, Shodan showed around 240 IP addresses with Langflow interfaces exposed to the internet. In surveying those IP addresses, 32% responded with connection errors, showing that they had been disabled since Shodan first detected them. From our previous use of Shodan we know that dead services are removed from results after about 3 weeks, suggesting quite a bit of turnover in Langflow instances– about a third of them are only exposed for a few days or weeks.

For the remaining Langflow instances, we queried two of Langflow’s API endpoints to determine which ones allowed unauthenticated access to account data: read flows, which returns a JSON representation of all workflows created in the instance, and read all users, which returns a list of users. The response rates for each endpoint were very similar: 59% responded with a 403 (forbidden) status code and 28% responded with various other statuses preventing access to the data. 13% of active Langflow instances allowed anonymous access to the API endpoint providing all flow data and 15% allowed access to the API to get users.

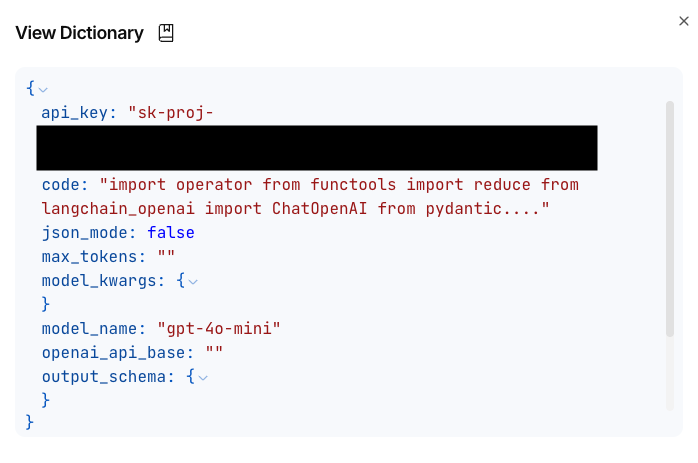

Additionally, Langflow provides APIs like “download file” that allow users to retrieve data files that have been uploaded for use in the flows. Downloading a file requires the flow id and the filename, which are provided by the aforementioned “read flows” endpoint. We further observed that flow definitions sometimes contain credentials like API keys and database passwords, expanding the impact of unauthenticated exposure. Other AI workflow tools we have researched prevent users from configuring instances without authentication and do not allow retrieval of credentials that have been entered into the system. Those design decisions can prevent and limit the impact of data leaks.

Discovery

With those APIs, we were able to survey the exposed Langflows and collect the flows from the 21 IP addresses leaking data. Amongst those, one stood out, returning a whopping 26.9MB JSON file describing its flows.

Examining the instance through the GUI, we found dozens of projects and flows, more than we could review manually. At this point, we extracted the “file_name” for each “flow_id” from that JSON response and used those to download a total of 1117 files. Almost all were small files, only a few kilobytes, with test data, public data sets, or duplicates of other files in the system. In total they added up to 242 megabytes. Out of over a thousand files, only a handful were sensitive, but those few contained personally identifiable information and confidential business information linked to a Pakistani government entity, making it imperative to report this data leak.

UpGuard first identified this IP address as an unauthenticated Langflow instance on 20 May, 2025. On 21 May, analysts discovered the presence of personally identifiable information and identified Workcycle Technologies as the entity most likely to be responsible. UpGuard contacted Workcycle via Linkedin that evening and by the next morning all access to the IP address had been removed.

Impact

Personally identifiable information

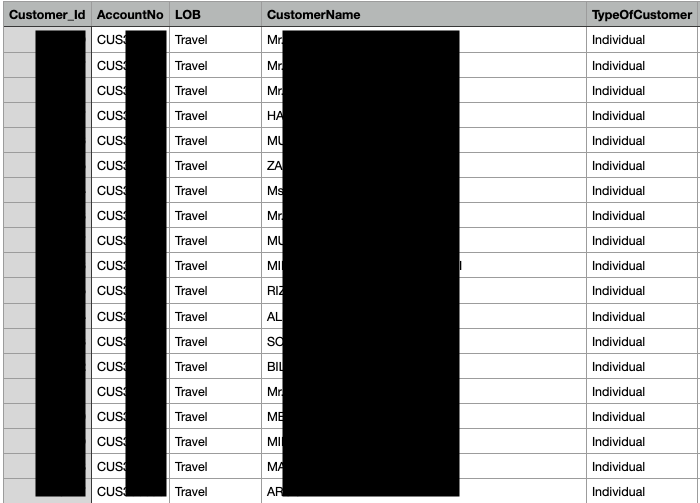

One of the files was a CSV named “2025-04-17_11-36-14_Copy of CustomerData21Mar25(Sheet1).csv” with 193,396 rows. The column headers were: Customer_Id, AccountNo, LOB, CustomerName, TypeOfCustomer, Customer Since, No_Of_Active_Policies, No_Of_Active_Products, Total_Active_Premium, No_Of_InActive_Policies, No_Of_InActive_Products, Total_InActive_Premium, DOB, Gender, City, address, Email, Channel, IncomeGroup, Annual_Revenue, ClubType_Id, clubtype, Credit_Limit, Credit_Period, Email, FATFCountry, Industry_Type_Id, Is_TPLCustomer, IsBackList, Occupation_Id, Organisation_Type_Id, Passport_No, OtherContryResident, OwnershipPEP, Payment_Mode, PEP, PEP_Reason, PEP_Relation, PEP_RelationReason, PublicFigure, Risk_Category, IsMigrated, lastsalesdt, product, SumInsured, BusinessType.

Deduplicating the CustomerName field yielded 96,699 unique names, roughly in line with the 96,082 unique values for Customer_Id and 96,010 uniques for AccountNo. The values for names had minor inconsistencies in style like the intermittent use of the Mr. or Mrs. honorific, some in all caps and some in sentence case, and some first names abbreviated to an initial, all of which are indicative of the stochastic nature of real data as opposed to synthetic data.

Data points revealing personal details were present for some but not all records, like 67,856 unique physical addresses and 21,922 unique email addresses. Gender, insurance product, and “SumInsured” were present for 99.8% of rows. Around 40% of the insurance products were for “takaful,” a Sharia-compliant form of mutual aid insurance available through Pakistani insurance company TPL. Several other files in the collection were named “TPL DATA.csv,” making it likely the data originated from the TPL insurance company. Curiously, 111,132 rows had passport numbers, but they were largely repeated, with only 180 unique values. It’s unclear which, if any, of these passport numbers are real and for whom.

Several columns related to whether the individual was a PEP, or politically exposed person, who are further classified as domestic, foreign, or related to a PEP. The Financial Action Task Force, the international bribery and corruption watchdog, defines domestic PEPs as: “individuals who are or have been entrusted domestically with prominent public functions, for example Heads of State or of government, senior politicians, senior government, judicial or military officials, senior executives of state owned corporations, important political party officials” and foreign PEPs as “persons who are or have been entrusted with a prominent function by an international organisation, refers to members of senior management or individuals who have been entrusted with equivalent functions.” Essentially these are social elites whose position provides them with greater opportunity for financial corruption.

The data set marked 945 individuals as PEPs. Google searches for the individuals’ names readily identified people who fit the names in the data set and the description of PEPs: CEOs, bank presidents, executives at critical infrastructure companies, grant writers for NGOs, and so on. Some email addresses associated with travel insurance plans identified travel agencies that were easily identifiable as real groups operating in Pakistan. The physical addresses we sampled also mapped to identifiable real locations for private homes.

Another file named “Final_Customer_Dataset_With_Insurance_Plans(Sheet1)” only contained 100 rows of data but gave more information on the PEP classification, with columns for PEP_Reason, PEP_Relation, PEP_RelationReason,PublicFigure, and Risk_Category. Out of this smaller but more detailed data set, 97 of the 100 dates of birth were unique values, ranging from birth years in 1949 to 2017.

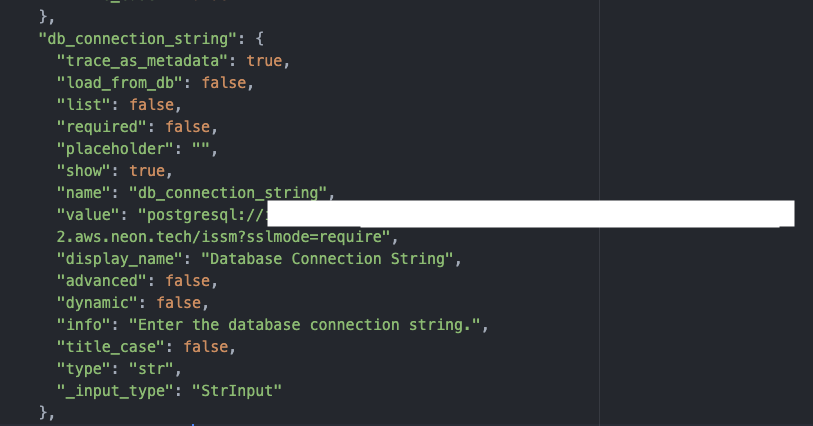

Credentials

Credentials could be retrieved from the flow definitions and the logs accessible in the user interface. Repeated throughout the collection were two significant credentials: an API key for an OpenAI account and a password for a Postgres database connection string hosted on neon.tech. These credentials could also be found in plaintext when viewing the logs for each flow in the Langflow GUI.

Confidential business data and the AI supply chain

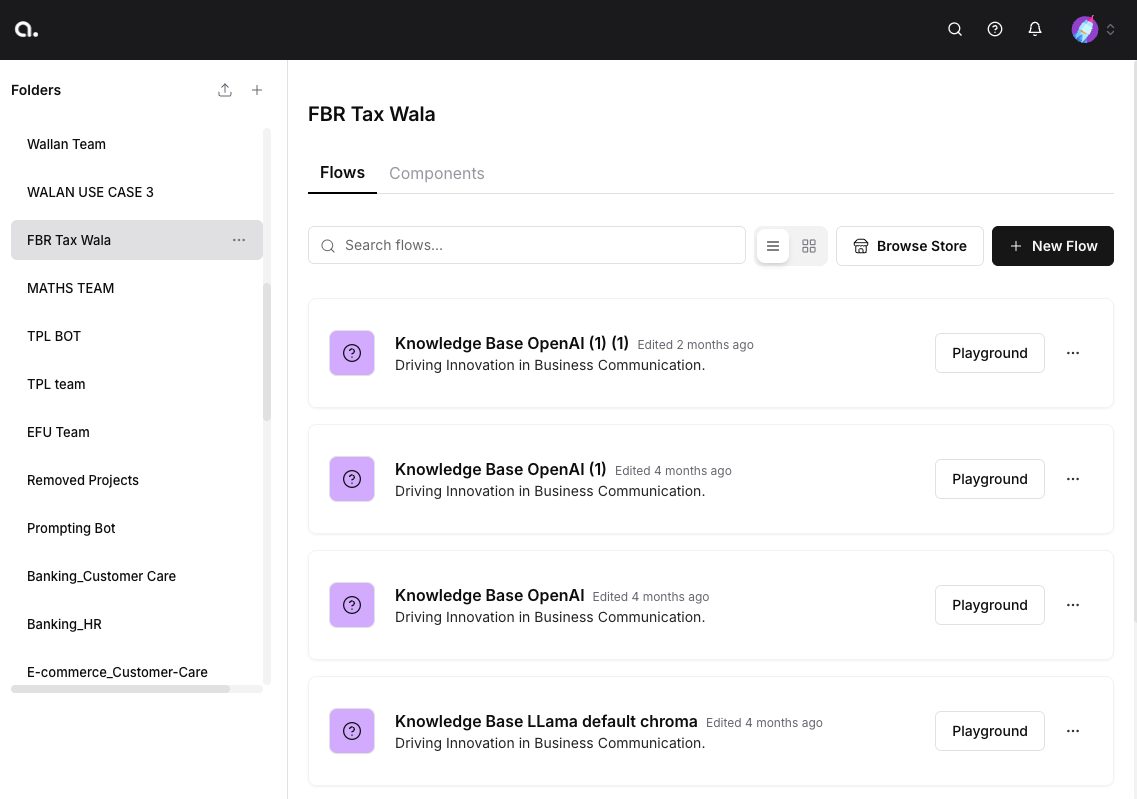

The Langflow instance was hosted on a subdomain of fintra.ai, which had other subdomains with active services, but no clear parent company. One of the documents in the collection, however, was a PDF “Functional Specification Document” describing a “Conversational AI for Tax Wala” for Pakistan’s Federal Board of Revenue last dated to 12/30/2024. The document had the logo and confidentiality notice for Workcycle Technologies. While Workcycle does not have a website, they do have a Linkedin page claiming 51-200 employees, leading UpGuard to notify them in our effort to secure the data.

The FSD also pointed to another company, ISSM.ai. One of the document’s authors had their email address embedded with an @issm.ai domain. Once we turned our attention to ISSM we saw that the document’s author is on ISSM’s leadership page and that their website touts similar projects they have done for Pakistan’s Federal Board of Revenue. ISSM also offers the same “B3” product seen on Workcycle’s Linkedin page.

Fintra.ai, where the Langflow instance was hosted, also has a “b3” subdomain, in its case bearing the name and logo of K-Electric, an energy company in Pakistan, with a redirect to Microsoft for authentication.

Workcycle and ISSM seem to be essentially the same company, employing the same leadership and offering the same products, though their respective web presences don’t disclose this relationship. Similarly, Fintra.ai seems to be a property managed by them, though again without an advertised relationship. “Sublo” is another entity in the mix, listed as one of Workcycle’s products, as ISSM’s partner in a 2021 blog post, and on Instagram as “formerly WorkCycle.”

All of that rebranding, while somewhat confusing when trying to figure out who to notify of a data breach, is also representative of a trend in the AI supply chain. Plentiful off-the-shelf AI software has reduced the barrier to entry for enterprising individuals to build an “AI app” of some kind almost overnight– and if one concept doesn’t work, they can pivot to another. When slower moving organizations like governments, banks, and insurers turn to them for AI expertise, the supply chains of core social institutions suddenly include these shadow vendors, where it is not clear what companies exist and for how long they plan to continue. The pace of change in the AI ecosystem provides a powerful inducement for small companies to continually make such soft pivots to stay at the forefront of the wave, creating new AI products and, sometimes more importantly, AI branding to match. The downstream impact of all that shuffling is the muddying of the supply chain for the institutions where vendor risk management matters most.

Conclusion

While the security lapse of a Pakstan-based technology firm might seem to have a limited impact, this case shows how data leaks can quickly reach the social strata with international implications. After a bout of armed conflict between India and Pakistan from May 7-10 of 2025, additional exposure of Pakistan’s industry, government, and military leaders creates risk well beyond their borders. In this case the data was promptly secured with no evidence of exploitation.

Langflow is a young technology; many of its users likely have not contemplated whether their account configurations allow public access to their data and what data types might be exposed. Through our research we hope to show what developers of AI technologies should consider in terms of secure application design, vendor selection, and account configuration. In this case, we have been able to show that it is possible to configure Langflow to expose data, that there are currently some Langflow instances doing so, and that in at least one case the data being exposed includes credentials and PII. Users of Langflow must be aware of these possibilities when creating their account configurations, storing credentials, and uploading documents with sensitive information. Perhaps more importantly, the clients who rely on such vendors must have visibility into their AI supply chain to ensure their data is not inadvertently leaked.

Protect your organization

Related breaches

Student Applications: How an Education Software Company Exposed Millions of Files

By Design: How Default Permissions on Microsoft Power Apps Exposed Millions

Sign up for our newsletter

Free instant security score

How secure is your organization?

-5.avif)

.jpg)

.jpg)