UpGuard previously discovered and reported on a data leak of logs for user traffic to leakzone.net, a forum for distributing stolen data and sharing hacking tips. In our first post, we analyzed major trends in the traffic logs to better understand the behavior of visitors to this site. Some subset of those visits would be from individuals engaged in the trafficking of stolen credentials and other illicit data, and thus our first investigation aimed to better understand threat actor behavior by looking at major trends in traffic origin.

In this follow-up, we approach the data from a different angle: first identifying recognizable organizations with owned IP ranges, and then analyzing patterns in the traffic from those IPs to Leakzone. This method of approaching the data highlights companies with relatively small amounts of traffic, but recognizable names in private industry, governments, and universities around the world. While the data available from the leaked logs does not provide explain the content of these requests or how they came to be logged, it highlights the need for threat monitoring to be aware of unlikely traffic to sites like the leakzone.

Welcome to the Leakzone

To recap the first part of our investigation, UpGuard discovered an Elastic database accessible to the internet. That database contained 22 million records of client requests to leakzone.net, a leak and cracking forum. Each request contained the source IP address, the IP address’ associated ISP and ASN, the destination domain (almost all of which were leakzone.net), the timestamp for the request, and the size in bytes. This data gives a fine-grained view of requests to the leakzone over a period of 28 days in June and July 2025.

ISPs of interest

The data set contained 8,8788 unique ISP names for companies around the world. To understand who was visiting leakzone.net, we tried to identify ISP names where the organization was not a provider of hosting or internet services to the public, and where we could thus infer that users at the named ISP were visiting or otherwise somehow initiating requests to leakzone.net. The major categories of organizations with dedicated IP blocks meeting that criteria were universities, governments, and name brand companies where we had some prior knowledge of their (non-telecom) business.

By combining AI analysis with our own efforts to eyeball the data, we were able to identify several organizations in each category, though these should not be taken as exhaustive; in our testing, both AI and human analysis were imperfect, though better together than alone. The matter was further complicated by the fact that our categories are not perfectly separate. In some parts of the world, internet service is a utility provided by the government. Likewise, government education departments, government-funded research projects, and universities are often connected, especially in China, home to a sizeable portion of the world’s population and IP addresses.

Non-telecom Companies

In picking through network names that were identifiable non-telecoms, many of them were familiar faces from the world of cybersecurity. While there are surely many more such companies monitoring leakzone.net from the anonymity of cloud infrastructure, these ones were identifiable from their IP address metadata. Even within the subset of cybersecurity companies, we have the problem of imperfect categorizability: Zscaler offers both network devices and threat hunting, making it hard to differentiate traffic from end users and threat intel collection.

Security companies

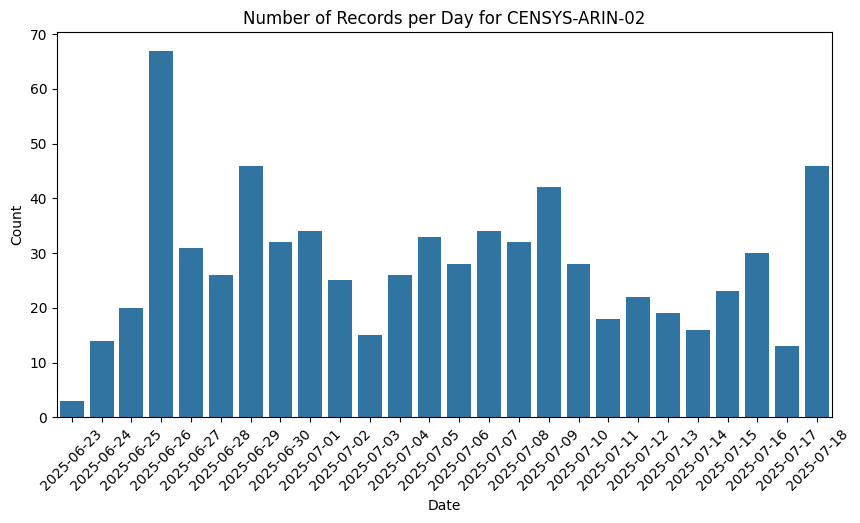

Censys is a clear example of an internet scanning vendor that would be generating automated requests to leakzone.net to collect information about their website infrastructure. And while their entries in the data set are not perfectly uniform, they have much less variance than we will see for some other networks that are not known internet scanners. Starting from our knowledge of Censys’ business allows us to establish a baseline for traffic patterns in this data set for a continuous, non-human data collection process.

Other companies

The names of some very large companies show up exactly once. That’s not enough traffic for a user to interact with the site, and it’s not clear why that would happen. (While it might make sense for J.P. Morgan and Jane Street to trade on threat intelligence, making one request per month is not enough for a meaningful signal). The data available from this leak is not sufficient to explain the cause of these very small amounts of traffic from private company networks.

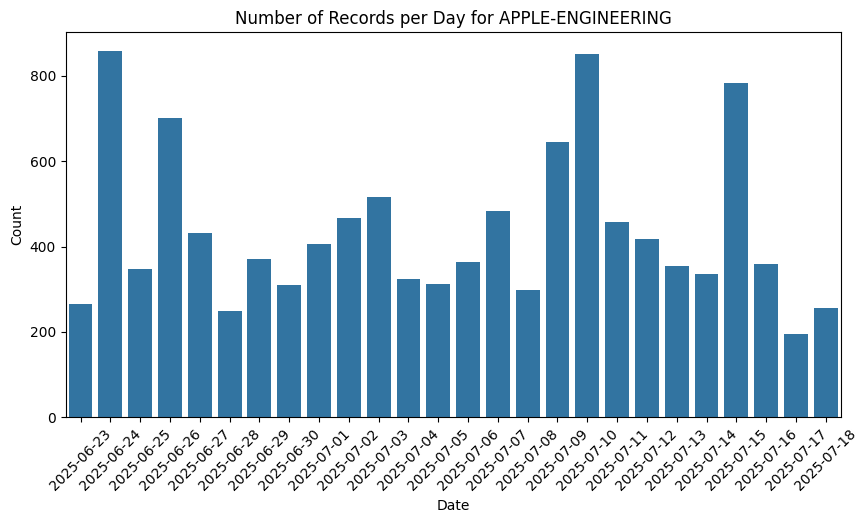

Like Censys, Ahrefs and SEMRush are companies with expansive internet scraping infrastructure to capture the same information search engines use about links between sites. The reason for their high volume of requests makes sense as part of their automated, indiscriminate mapping of the internet. Apple’s reason is not obvious, but their traffic pattern is similar to that from Censys above and thus reasonably classified as internet scanning or threat intelligence collection of some kind.

Governments

The list of governmental bodies illustrates some of the challenges in neatly classifying ISPs as government run telecoms versus government networks. Afghan Telecom is a public telecom, but not all of their IP addresses are marked as part of the “government communication network” ISP. The ministries related to technology, research, and education likewise might offer portions of their network for outside use.

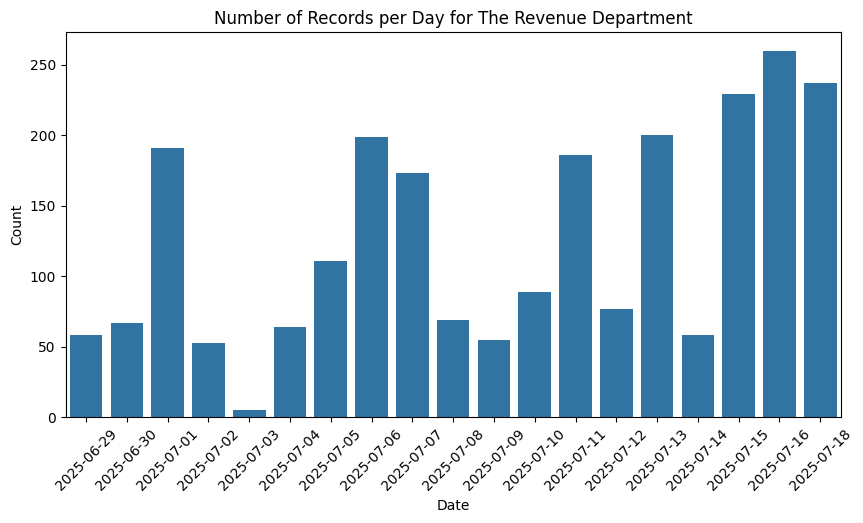

The question, then, is why users on each of these networks is interacting with leakzone.net. Like the security and SEO vendors, the ministries related to technology and education may have users performing similar scanning as part of research projects. One way to test that hypothesis is to look at patterns in the request frequency.

The pattern of requests from The Revenue Department shows more variance than that of Censys or Apple, with intermittent spikes on some days and troughs that deviate further from the average. Is this an automated collection process that averages out over time, or is it evidence of a non-automated system? Whereas Apple’s traffic seemed too consistent for a human, here there is more doubt.

At a further extreme, the 40 requests from the network of The Russian Federal Guard all take place over the course of a few seconds on one day. That could be an automated system, but the volume of requests is really too small to be useful as a monthly scrape of intelligence. It could also represents a human user briefly visiting the site from their work network where they protect Russia’s highest ranking political officials and nuclear briefcase before realizing they need to disconnect.

Universities

Of the organizations we were able to classify, universities far outnumbered governments or non-telecom companies. There are a few reasons for this observation: universities are more likely to have their own IP ranges than non-telecom companies, giving them more identifiable networks, and the users of university networks include researchers and university students, populations more likely to be investigating the world of data leaks. University students are also, shall we say, less risk averse than other populations.

The most active is clearly MIT’s public wifi, where the total activity over the 28 day period is the results of intermittent spikes of random sizes. The comparison to other networks isn’t entirely fair– public wifi is, well, public, and in that regard it is open for anyone to use who is in physical proximity to MIT.

The pattern of intermittent spikes is even more pronounced than in example The Revenue Department. This pattern of behavior is clearly not an automated, continuous process like seen from internet scanner. It likely indicates either human users interacting with the site or running manually triggered data collection scripts on particular days but not others.

Conclusion

Identifying known company names in the IP metadata allows us to start from the predictable behavior of internet scanning companies like Censys or SEMRush and confirm that automated scanning produces relatively consistent traffic across time. That baseline can be used to compare to other traffic patterns to guess at whether they are performing automated data collection or ad hoc interactions more indicative of human users. It seems likely that most of these organizations do not have internal actors browsing or contributing to the corpus of leaked data on the Leakzone, and in some cases the traffic volume is too small for any meaningful exchanges. And yet, that uncertainty shows why so many companies are monitoring the Leakzone for intelligence– even if there is only a tiny chance of a real threat, you'd rather be sure.

Protect your organization

Related breaches

Student Applications: How an Education Software Company Exposed Millions of Files

By Design: How Default Permissions on Microsoft Power Apps Exposed Millions

Sign up for our newsletter

Free instant security score

How secure is your organization?

.jpg)

.jpg)