Emerging Risks: Typosquatting in the MCP Ecosystem

Model Context Protocol (MCP) servers facilitate the integration of third-party services with AI applications, but these benefits come with significant risks. If a trusted MCP server is hijacked or spoofed by an attacker, it becomes a dangerous vector for prompt injection and other malicious activities.

One way attackers infiltrate software supply chains is through brand impersonation, also known as typosquatting—creating malicious resources that closely resemble trusted ones. Our research asks: could this same method compromise the MCP ecosystem?

The anatomy of a "Squatting" attack

To answer that question, we need to examine how these attacks actually work. A successful "squatting" attempt requires two ingredients:

- Accessibility: The attacker must be able to create a malicious resource on a platform where users are looking for tools. (e.g., Anyone can register an unclaimed web domain).

- Human Error: The user must make a mistake while navigating to that resource. (e.g., A user accidentally types ‘gogle.com’ into their browser instead of the intended site).

In the MCP ecosystem today, we can prove that both conditions are being met. Users are already entering server names with "fat-finger" typos, and open registries exist where malicious actors can distribute code to exploit those exact mistakes.

Misspelled context protocol servers

In a recent research project, we analyzed 18,000 Claude Code settings files collected from public GitHub repositories. In addition to permissions for the commands Claude can run, these files also contain the MCP servers that each Claude instance can utilize.

When we aggregated the configurations for MCP servers and browsed through their names, we noticed some interesting outliers: server names that, at first glance, appeared to be duplicates but were, in fact, slight variations on other server names. In other words, these entries in Claude permissions files validated that the human error in name entry that makes typosquatting successful exists on the user side of the MCP ecosystem.

More subtly, many entries for MCP server names contained variations on casing and separator characters. Currently, the MCP ecosystem hasn't settled on a standard for handling capitalization [1]. There is no perfect way to prevent problems caused by human error, with trade-offs either way:

- The "Silent" Match: If MCP names are not case sensitive, and a system automatically converts everything to lowercase and/or removes separators (e.g., treating "UpGuard" and "upguard" as the same or “upguard” and “up_guard”), a typosquatted server could be deployed alongside a legitimate one without the user knowing that the system sees their names as the same.

- The "Lookalike" Identity: If MCP servers are case-sensitive, an attacker can register the lowercase version of a famous brand (like hubspot vs. HubSpot). Since there is no central registry to enforce unique ownership, both can exist simultaneously. Users might install the lookalike server by entering the wrong casing.

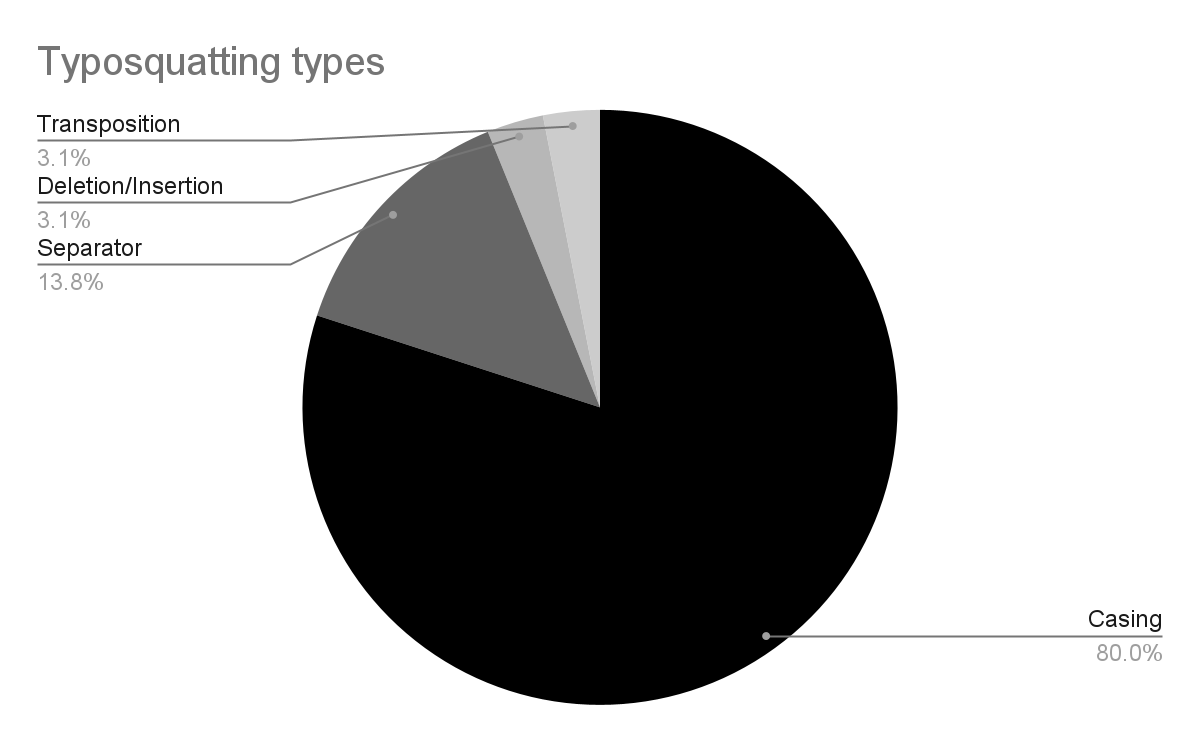

Differences in casing were by far the most common form of variation. Across the entire ecosystem, however, the other forms of MCP server nam confusion could present a meaningful attack vector.

These examples prove a critical point: AI agent systems are human-configured, and humans are prone to mistakes. While a misspelled name seems minor, in an AI ecosystem, it’s a direct invitation for an attacker to step in.

Unmoderated registries

For an attacker to exploit a typo, they need a place to host their "lookalike" server where a user is likely to find it. For users browsing the web, this is a fake domain designed to catch users who misspell a URL. In the software world, it’s a malicious package on registries like NPM or PyPI.

These package registries are a perfect analogy for the risk we see in MCP today. While these platforms have some controls, attackers have become experts at "seeding" them with malicious code that mirrors popular tools. When a developer makes a mistake during an install command–like installing “acitons/artifact” instead of “actions/artifact”–they are actually deploying the attacker's code into their local environment.

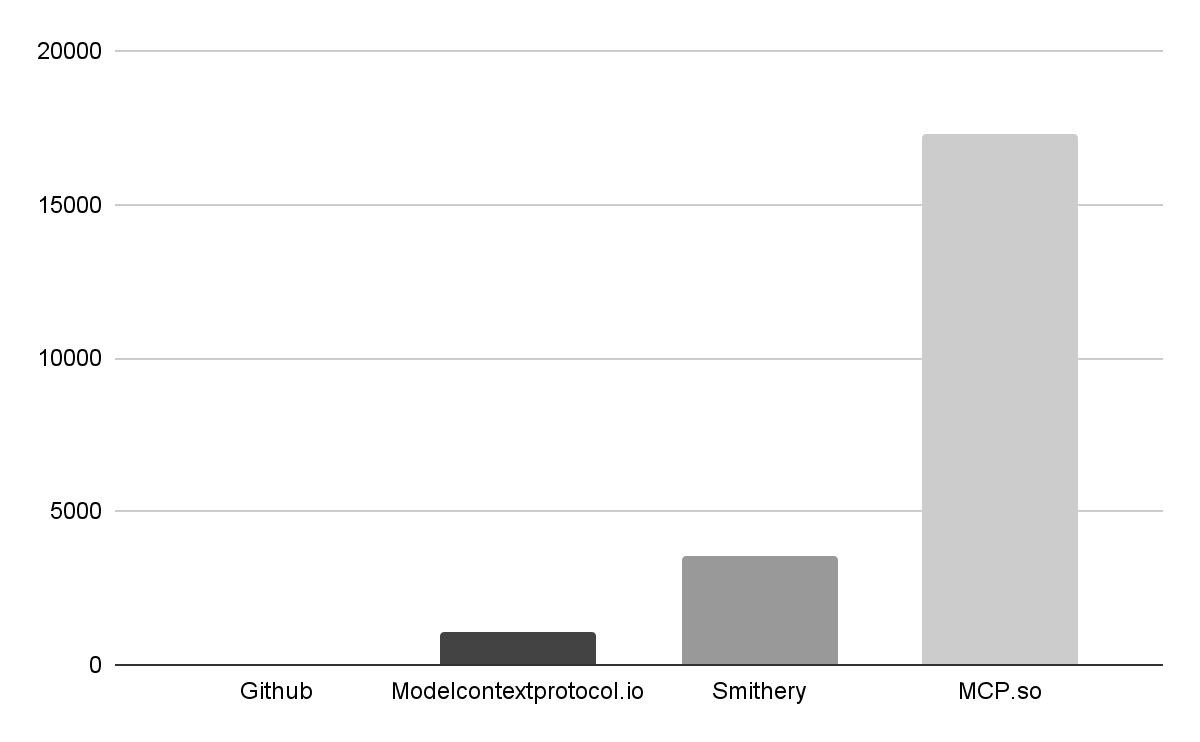

For MCP servers, the delivery mechanism is currently even more vulnerable. Because the ecosystem is so new, registries are unstandardized and vary wildly in how they vet new uploads. (And might even rely on the NPM registry for artifacts). We analyzed the four most popular registries to see how easily an attacker could "squat" on a brand name.

The results show the trade offs between security and moderations versus openness and growth.

GitHub MCP Registry

- Status: Highly Moderated / Official Only

- This registry is the gold standard for security, but has the smallest selection, containing only 57 official entries from established service providers. The threat of an attacker-controlled server slipping into this list is very low, making it a safe, though limited, reference point.

Smithery.ai

- Status: Community Marketplace / Mixed Moderation

- With over 3,500 servers, Smithery is a popular hub that allows community contributions. While they use an “official” badge to verify vendors, our sample of 847 servers showed that only 8% of the servers carried this badge. The remaining 92% are unverified, creating a large surface area for potential impersonation.

“Official MCP Registry” (modelcontextprotocol.io)

- Status: Emerging / Inconsistent Verification

- Launched in late 2025, this registry hosts about 1,000 servers. It currently lacks a formal "verified" property. While namespaces can hint at a server's origin (whether it is published by a vendor or a Github user), the lack of a clear visual trust signal makes it difficult for the average user to distinguish between a community project and a corporate tool.

MCP.so

- Status: Unmoderated / High Risk

- As the largest collection with over 17,000 servers, MCP.so represents the "Wild West" of the ecosystem. While some servers are marked as “featured” or “official,” the criteria for these labels are vague. The sheer volume of unvetted code here makes it the primary target for attackers looking to seed the ecosystem with lookalike servers.

Brand impersonation via MCP server

The massive gap between GitHub’s 57 official servers and MCP.so’s 17,000 entries is filled almost entirely by community contributions. While this community-driven growth is a strength of the ecosystem, it also presents creates fertile ground for brand impersonation.

Because MCP servers are lightweight and easy to build—often with the assistance of AI coding agents—an attacker can easily create a project that looks like an established brand. These registries then provide the perfect distribution method to connect those malicious servers with unsuspecting users.

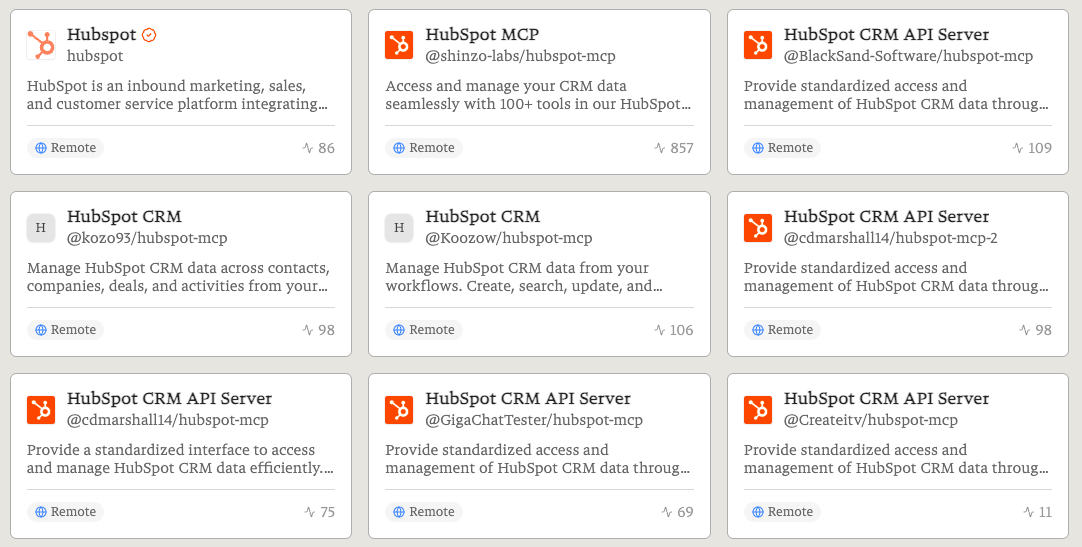

On one hand, this is expected; developers naturally want to share tools for their favorite platforms. However, this creates an environment where a user looking for an "Official HubSpot" server might see nine different "HubSpot" options—all of them receiving active traffic—but only one of them actually is provided by HubSpot.

The "Lookalike" audit

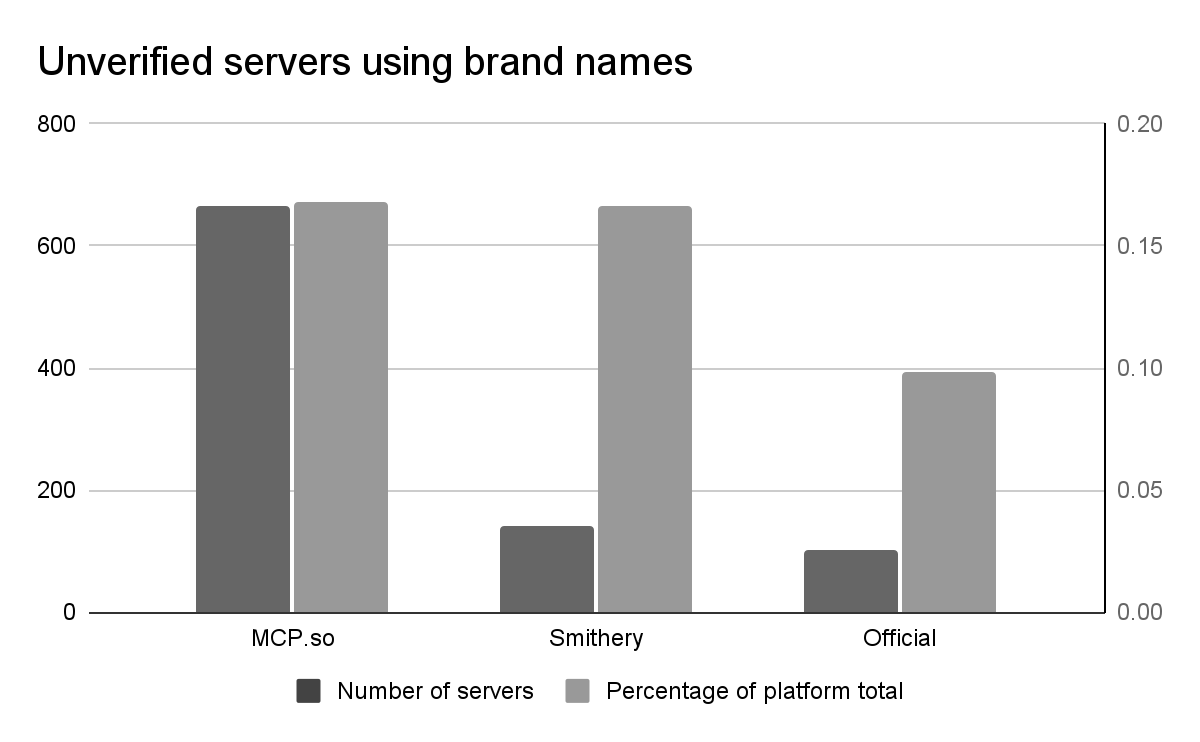

To measure how frequently registries are populated with servers that could be used for brand impersonation, we extracted 43 brand keywords (such as “GitHub,” “Supabase,” and “Tableau”) from verified servers and searched for matches among the unverified ones. The results were startling:

- The Multiplier Effect: For every official brand server, we found between 3 and 15 unverified lookalikes using the same brand names.

- The Volume: lookalikes for just these brands account for 10–16% of all MCP servers across the registries we studied.

MCP.so has both the highest raw number of MCP projects that look like verified projects. The “Official MCP Registry” currently has the fewest, though that could increase if it gains the same kind of mass adoption as the registries launched before it.

Remote MCP servers depending on untrusted Github users

MCP servers operate in one of two environments, and each presents distinct security tradeoffs:

- Local Servers: These are code artifacts that a user downloads and runs on their own machine. The risk of brand impersonation here is traditional but severe: if the locally executed code is malicious, it has immediate access to the victim’s system.

- Remote Servers: These are hosted by a third party, relieving the user of the need to run the server themselves. While convenient, this requires integrating with a service running elsewhere. The remote address must be trusted.

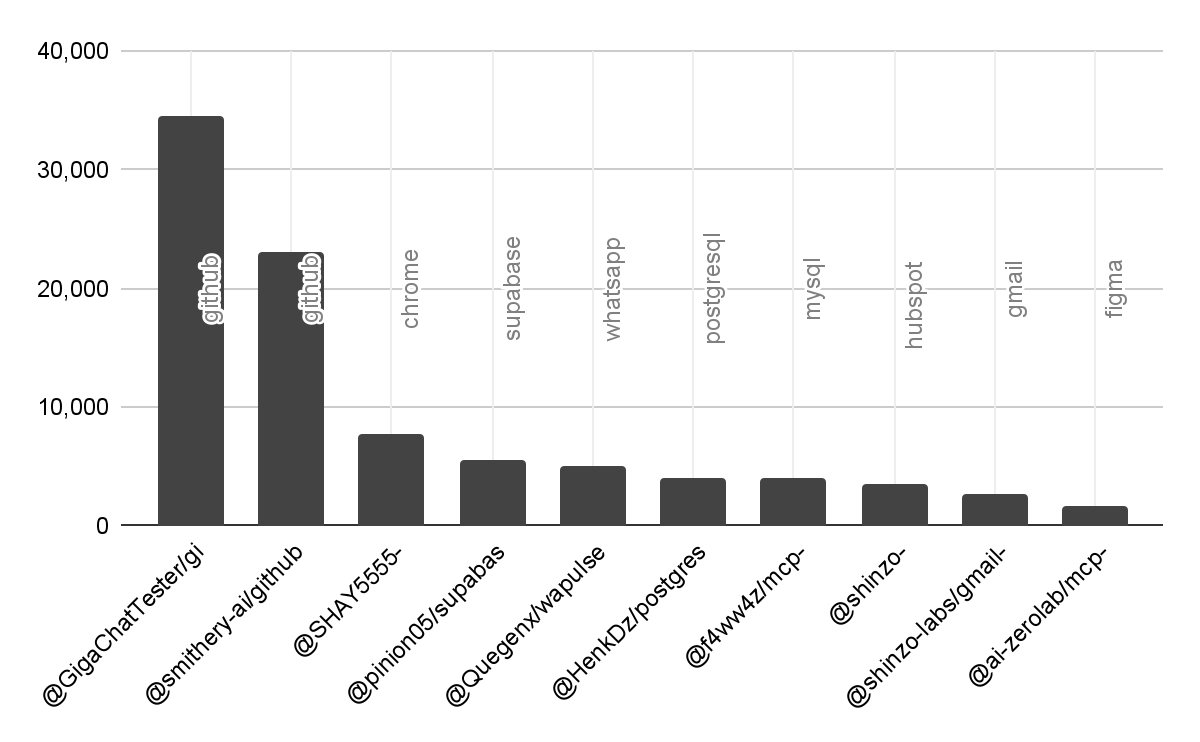

In theory, remote MCP servers hosted by a reputable organization can provide assurance to the end user that they aren’t running malicious code. However, examining usage data of Smithery’s remote servers shows that some of the most active servers rely on code from community Github users, making the security of those user accounts part of the supply chain for end users of the remote server.

For example, when searching for GitHub MCP servers on Smithery, the official GitHub server is listed alongside several others. The most commonly used server at the time of research is hosted by Smithery but deploys code from a repo owned by Github user “GigaChatTester.” In other wose, the account security of GigaChatTester’s personal GitHub account is a load-bearing part of the software supply chain for thousands of developers.

This is not an isolated case. Other MCP servers based on GitHub repositories managed by individuals—rather than the companies behind the services—regularly receive thousands of calls per month. As AI agents gain more autonomy, the industry must move toward a model where the "who" behind the code is as verified as the code itself.

Conclusion: A susceptible ecosystem

The presence of misspelled and misconfigured MCP settings in 18,000 public files isn’t just a minor technicality; it’s empirical evidence that AI agent systems are vulnerable to typo-based attacks.

To stay ahead of these emerging threats, organizations need a multy-layered approach. Solutions like UpGuard’s Breach Risk can help detect brand impersonation in the MCP ecosystem and beyond, and User Risk can detect shadow AI usage that might leak data to untrusted vendors.

As we transition from early experiments to a reality where AI agents have widespread permissions—such as the ability to execute code or deploy to GitHub—the industry must prioritize better verification standards for these servers. Ultimately, the responsibility lies with the organization: users must be as careful with their MCP configurations as they are with their passwords, and ensure that only verified, trusted servers are allowed in their environment.